Expand your horizons with these variations on Chinese food in San Francisco

Outside of China, Chinese food ventures far beyond Americanized dishes like chop suey and General Tso’s Chicken. This remarkably versatile cuisine – born of centuries of immigration, persecution, and scarcity – has been reinvented repeatedly as required by custom and circumstance. Here we explore the history of three very different cultural takes on Chinese food, and where you can find them in the Bay Area.

A few featured dishes of Red Hot Chilli Pepper restaurant in San Carlos, Hakka noodles, left, gobi manchurian, center, and spicy paneer, right.

Nicola R Parisi/Nicola ParisiFor Mission resident Saptarshi Guha, who developed his palate in Kolkata (formerly known as Calcutta), Chinese food means gobi Manchurian: deep-fried cauliflower florets draped lightly in a spicy, tangy sauce. “It is an adored dish, and it absolutely must be crispy. That is rule number one,” he explained. “If you stop at one bite, that is not good.”

While historical details of this cuisine can be difficult to pin down due to India’s penchant for oral history, New Delhi journalist Sharanya Deepak verified many aspects of the food’s origin story for a 2017 Vice article, “Inside the Birthplace of Indian-Chinese Cuisine.” Kolkata’s first Chinese immigrants, mostly Cantonese speakers from the Guangdong region, arrived in the late 1700s to work in sugar mills. During the 19th century, while trade was flourishing under British rule, many took up crafts such as shoemaking and carpentry. To nourish these workers with a taste of home, Hakka-speaking Chinese immigrants began opening small restaurants. As Indians discovered the eateries, Chinese proprietors altered their traditional cooking to cater to the Indian affinity for spice and oil.

By the 1970s, the cuisine had spread to big cities like New Delhi and Bombay (now Mumbai). According to Deepak’s research, India’s “Manchurian” style of cooking was invented at China Garden, one of Mumbai’s first Chinese restaurants, when chef Nelson Wang floured and deep-fried cubes of chicken before dipping them in a heavily spiced sauce punched up with chili peppers. Today, nearly every Indian Chinese restaurant menu features a generous helping of vegetarian and meat-based “Manchurian” dishes, including chicken, shrimp, mushrooms, baby corn, and fried vegetable balls or “coins” made primarily of cabbage. Despite the moniker, none of these dishes resembles traditional Manchu cuisine. Likewise, the Kolkata-created “Schezwan sauce” — a co-mingling of ginger, garlic, onions and several Indian spices in a heavy pour of oil — bears no resemblance to Sichuan cuisine, beyond the Indianized pronunciation.

Nevertheless, Indians consider Manchurian and Schezwan dishes to be quintessentially Chinese, along with the required accompaniments of Hakka noodles or Indian fried rice, which absolutely must be made from basmati, according to chef Bharat Dhamala, founder of Red Hot Chilli Pepper in San Carlos and Fremont. “We always make fried rice with long grain basmati rice, which is normally used for biryanis,” instead of the short-grain, sticky rice used by traditional Chinese cooks. “Long grain rice has much less starch, so when you strain it and boil it, it becomes very fluffy. And that’s how we Indians love it,” he explained.

Chef Bharat Dhamala, left, and owner Snehal Patel, right, of Red Hot Chilli Pepper restaurant in San Carlos.

Nicola R Parisi/Nicola ParisiIn fact, some of his restaurant patrons love it so much, they regularly drive an hour or more to indulge their cravings for fluffy fried rice, Hakka noodles, chilli chicken, vegetable coins in Manchurian sauce, and other Indian Chinese dishes they grew up with. Though the terms Indian Chinese and Indo-Chinese are often used interchangeably, this standalone cuisine is markedly different from the dishes served in Indo-Chinese fusion restaurants, where Nepalese momos share the menu with chicken tikka masala and lamb biryani.

“It’s totally different” from the fusion fare, says Dhamala, who also runs four Indian Chinese restaurants in Kolkata. “Bringing this food to America was always my dream. Whenever Indian people living in the U.S. would come to my restaurants in Kolkata, they would say, ‘We miss this food! Why don’t you open in America?’ So one fine day, I opened Red Hot Chilli Pepper in San Carlos. It was so popular that I now have four restaurants across America,” including locations in Dallas and Chicago.

Peruvian Chinese Food, a.k.a. Chifa

The duck fried rice with house hot sauce at El Porteño II Restaurant & Bar.

Nicola Parisi/Special to SFGATEThe evolution of Chinese food followed a similar path in Peru, where it is known as Chifa. According to UC Berkeley associate professor Lok Siu, a cultural anthropologist who studies the Asian diaspora in Latin America, Chinese contract laborers began arriving in Peru and Cuba in 1849 to work the sugar and cotton plantations, as the slave trade was being abolished.

The brutal treatment of these indentured workers led the Chinese government to shut down ports for labor export to Latin American in the 1870s. But a second wave of Chinese workers arrived in later years to build railroads and harvest guano, joining the more than 100,000 Chinese immigrants already living and working in Peru.

Upon earning release from their contracts, many Chinese immigrants took domestic jobs in the kitchens of wealthy Peruvians, where their employers developed a taste for the new flavors they introduced. Others opened small restaurants known as fondas, where the cuisine built on ingredients familiar to the Peruvian palate while also catering to Chinese customers. This cultural mash-up produced lomo saltado (“jumped loin”), the Peruvian staple dish that features strips of beef loin, potatoes, and onions stir-fried with garlic, ginger, soy sauce and Peruvian chili peppers, and plated with rice.

According to Peruvian anthropologist Humberto Rodriguez Pastor, “The Peruvians heard the Chinese pronounce the expression ‘chi-fan,’ which means to eat rice, or simply a call to approach,” as they greeted each other before entering the fondas. The Spanish speakers localized the pronunciation and began referring to these fondas as “chifas.” They also localized “chau-fan,” a Chinese term for fried rice, to describe their own version: “arroz chaufa.” The dish is so popular that Peruvians created the term “chaufero” to describe a cook who specializes in making it.

In his 1993 publication, “La Pasión por el Chifa,” Pastor estimated there were 4,000 chifas in Lima, employing some 32,000 people. In 2018, food writer Carlos C. Olaechea reported in Food52, “Currently there are over 6,000 chifas in Lima alone. Some sources claim that there are more chifas in Peru than any other type of restaurant.”

During the three months I spent exploring Peru in 2019, I saw Peruvians from the Amazon to the Andes flock to these restaurants, particularly on Sundays, where they shared family-size portions of fried wontons covered in sweet and sour sauce known as kam lu wantan, stir-fried meat and vegetables tossed with spaghetti noodles called tallarín saltado, and pollo chijaukay, crispy chicken morsels nestled in a mild, salty sauce thickened with chuño (potato starch). The meal was always accompanied by ají de rocoto (a spicy red sauce made from rocoto peppers) and typically washed down with Inca Kola. I dined with locals in chifas in Cusco, Aguas Calientes (Machu Picchu), Arequipa, Nazca and Chiclayo. They were as ubiquitous as ceviche and Pisco.

Perhaps this explains the deep devotion of El Porteño‘s customers. Victor Orteño, whose family owns and operates the two restaurants in San Francisco’s Excelsior and Mission districts, said they attract local immigrants from Peru who can’t quite satisfy their craving for a taste of home at American Chinese restaurants.

“When you’re used to a cuisine being prepared in a certain way, it’s a huge letdown to order something that doesn’t meet that standard,” he explained. “When they go to an American Chinese restaurant, it seems off. Not in a bad way; it’s just different. Our customers are looking for that homey feel. They tell us they miss home so much, especially now that they can’t go back because of COVID, and this is the closest thing they can get to the taste of home.”

El Porteño II Restaurant & Bar.

Nicola Parisi/Special to SFGATEThe Orteño family strives to provide the comfort that only Peruvian flavors can bring to chifa. They import globe-shaped rocoto chili peppers to make their own ají de rocoto, which is the perfect accompaniment to one of their house specialties, chaufa de pata (duck fried rice). They even grow their own huacatay, an aromatic herb used in the ají de rocoto that tastes like a combination of sweet basil, tarragon, mint and lime.

The name El Porteño is more than a play on the family’s surname; it refers to the former occupation of the family patriarch, who worked at a shipping port near Lima before immigrating to the U.S. These are the only Peruvian restaurants in San Francisco offering a full chifa menu, which is complemented by a seafood-centric “criollo” menu of typical Peruvian fare, including pollo a la brasa (rotisserie chicken) and, of course, lomo saltado.

Islamic Chinese Food

Freshly made dumplings at Old Mandarin Islamic Restaurant.

Nicola Parisi/Special to SFGATEUnlike chifa and Indian Chinese food, which were developed by Chinese immigrants in their adopted countries, Islamic Chinese cuisine follows halal standards and was developed within mainland China by Muslim immigrants. “Islam and halal food traditions were introduced to China in the early seventh century through the Central Asian, Arab, and Persian merchants, soldiers, and missionaries who trekked the treacherous ancient overland and maritime Silk Road trade routes,” wrote Abdelhadi Halawa, associate professor at Millersville University in Pennsylvania, in “Acculturation of Halal Food to Chinese Food Culture through the Ancient Silk Road and Hui Minority Nationality.”

Relegated primarily to the Xinjiang region of northwest China, these Muslim immigrants continued the cultural and food traditions they brought from home. “While China has 10 ethnic groups which are predominantly Muslim, two of these are most prominent: the Uighurs, who are of Central Asian descent, which live in Xinjiang, and Hui Muslims, which are a mixture of Arab, Persian, Turkish and Chinese descent,” said Muhammad Aurangzeb Ahmad, who publishes the Islam in China blog under the pen name Wang Daiyu. During the ninth century, a progressive emperor of the Tang Dynasty granted Muslims more freedom of movement, “and the Hui seized the opportunity to migrate to other regions, which saw the emergence of distinctly Hui cuisine.”

While the Hui from Xinjiang moved overland, other Middle Eastern merchants and missionaries crossed the Indian Ocean to arrive by sea to southwestern Chinese coastal cities such as Canton (present-day Guangzhou). Some eventually settled northward, near modern-day Beijing.

Whether they arrived by land or sea, their embrace of the Mandarin language and willingness to assimilate into Chinese culture allowed the Hui to continue practicing their religion without overt persecution. Many drew on their merchant skills to start halal food businesses, providing meat raised and slaughtered according to strict Islamic guidelines.

In addition to lamb, mutton, wheat and spices like cumin and chili powder, Halawa wrote, “the major contribution that Muslims made to the Chinese food culture is the introduction of different cooking styles such as steaming, roasting, stewing, and braising of food.”

Some scholars also believe they introduced noodles to Chinese cuisine. “Noodles are 100% Muslim, no doubt about it,” said Halawa. “They originated in the Northwestern Uighur region [where wheat grows readily] and did not even exist in China” before Muslims arrived. But according to Ahmad, “while there are no records of noodles in the modern sense that predate Muslims in China, there is evidence of a noodle-like dish in China that was discovered recently that predates Islam by many centuries.”

By the 14th century, Muslims had settled throughout the entire country, and “a number of Chinese cities in the Qing dynasty, and especially in the 19th century, had renowned halal restaurants that catered to Muslims and locals,” according to the China Heritage Project at Australian National University.

In today’s China, halal cuisine has gone mainstream, particularly in Beijing, where Muslim street vendors grill spicy cumin lamb skewers over an open flame and sell them to passersby. Halal food stalls also offer beef noodle soup, another quintessential Muslim dish, which features hand-pulled Lamian noodles. Dozens of halal restaurants draw Beijingers of all backgrounds, who seek them out for both the flavorful cuisine and their reputation for notoriously sanitary conditions.

Bay Area residents can find Beijing-style Muslim Chinese food in San Francisco’s Sunset District, where Old Mandarin Islamic Restaurant has been serving it for 24 years. Shuai Yang started working in the restaurant as a teenager in 1997, when his Muslim Chinese parents opened it with a friend, 10 years after immigrating from China. Like many immigrants, they struggled with English and didn’t have much money. But his father did have experience as a cook. “So, the best thing for immigrants to start is either a restaurant or construction, or some small business you can handle yourself,” he explained.

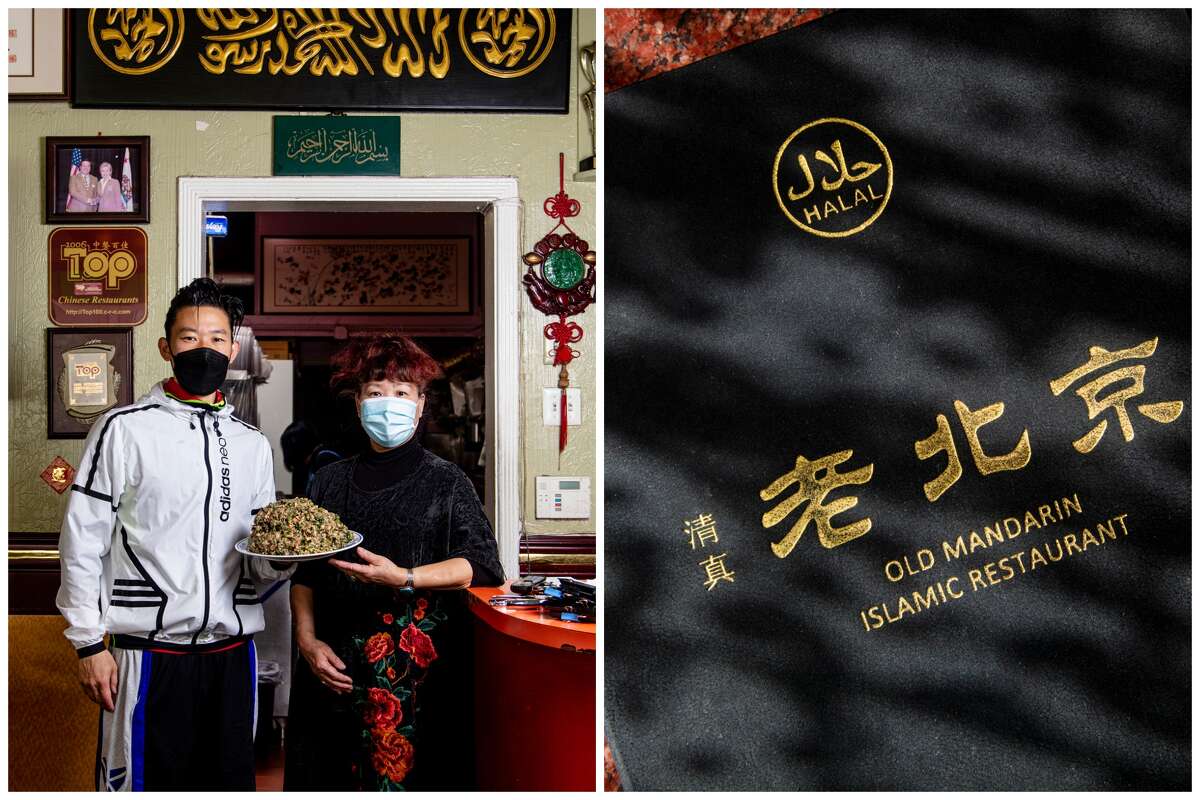

LEFT: Shuai Yang, left, and Feng Wang, his mother, right. RIGHT: A menu cover.

Nicola Parisi/Special to SFGATEFor the first few years, business was slow and mostly limited to a few dozen Muslim patrons per month. But once they made a name for themselves, business picked up, and local food writers discovered them, leading to welcome publicity. As a result, the nearly 40-seat restaurant started drawing a steady stream of Chinese families familiar with the cuisine, Middle Easterners who love Chinese food and follow a strict halal diet, and local residents who discovered the restaurant through word of mouth or stumbled upon Chinese Muslim food during a visit to Beijing.

Old Mandarin’s heavily spiced cumin lamb stir fry is succulent and deeply satisfying, with no hint of gaminess. In addition to both hot and cold noodle dishes seasoned with a variety of flavors from sesame to mushroom to dark bean paste, a handful of noodle soups are on offer, including five spice beef and braised lamb brisket.

Besides staple Islamic Chinese dishes, the restaurant also serves a few traditional dishes from China that aren’t often found on American Chinese menus, such as the crispy, refreshing shredded potato with jalapeño and the comforting stir-fry scrambled eggs with tomato. And no visit to Old Mandarin would be complete without trying the crack fish with spicy numbing sauce, a traditional Sichuan dish known in China as water boiled fish. According to Yang, for the first few years it was on the menu, only Chinese patrons ordered it. Then, a group of his friends from high school saw it on another table, and one said, “Damn, that looks good!”

After tasting the tender chunks of flaky white fish perched on a bed of Napa cabbage submerged in a bubbling broth slicked with spicy chili oil, the friend said, “That’s delicious, but it has a terrible name. You should call it crack fish.” Yang said, “As soon as we started using that name, people started ordering it.” Fifteen years later, it remains one of the most popular items on the menu.

The versatility of Chinese food sets it apart from other cuisines, such as French food, which is highly prescribed and requires a multitude of specialized equipment. To make authentic French food, “You need a sauté pan, a crepe pan, a sauce pan and a special fish poaching pan,” explained Grace Young, a cookbook author known as the “Stir-Fry Guru,” who grew up in San Francisco’s Chinatown. “But to make Chinese food, all you need is a wok. Stir frying truly is the supreme culinary chameleon. It can adapt itself to whatever environment it finds itself in.”

Which brings us back to the question: What makes Chinese food Chinese food? Why is it so adaptable to so many different cultures and ingredients? Young attributed it to the fact that Chinese cooking is rooted in scarcity. “Whatever the emperors and warlords had, the vast majority of Chinese people spent their lives short of fuel, cooking oil, utensils and even water,” she said, quoting author E.N. Anderson from “The Food of China,” a comprehensive account of Chinese food from the Bronze Age to the 20th century. “I think that really does sum it up. With one wok, you can do everything: steam, boil, poach, pan fry, stir fry, deep fat fry, braise and smoke.”

This history of scarcity necessitated both a willingness and an ability to make do with — and embrace — available resources. That flexibility has served the diaspora well, as Chinese immigrants altered the cuisine of their homeland to incorporate local tastes, techniques and ingredients, no matter where they made a new home abroad. And within their own borders, they incorporated foreign food traditions introduced by Muslim immigrants.

Young’s award-winning cookbook, “Stir-Frying to the Sky’s Edge,” chronicles crossover recipes from around the globe, including Chinese Trinidadian stir fried shrimp with rum, Chinese-Jamaican jerk chicken fried rice, and stir fried bok choy with pancetta from France. The versatility of this cuisine just goes to show that, no matter where your taste buds were attenuated, there exists a version of Chinese food that has been custom-designed to tantalize them.

Red Hot Chilli Pepper has two locations in the Bay Area: 1125 San Carlos Ave. in San Carlos and 43321 Boscell Road in Fremont. El Porteño has two locations in San Francisco, 5173 Mission St. and 2293 Mission St. Old Mandarin Islamic Restaurant is located at 3132 Vicente St. in San Francisco.

Renée Alexander is a communications consultant and freelance writer specializing in food, booze, travel and culture. www.grassrootspr.com