Victoria Chang’s ‘Dear Memory’ explores memory’s links to identity : NPR

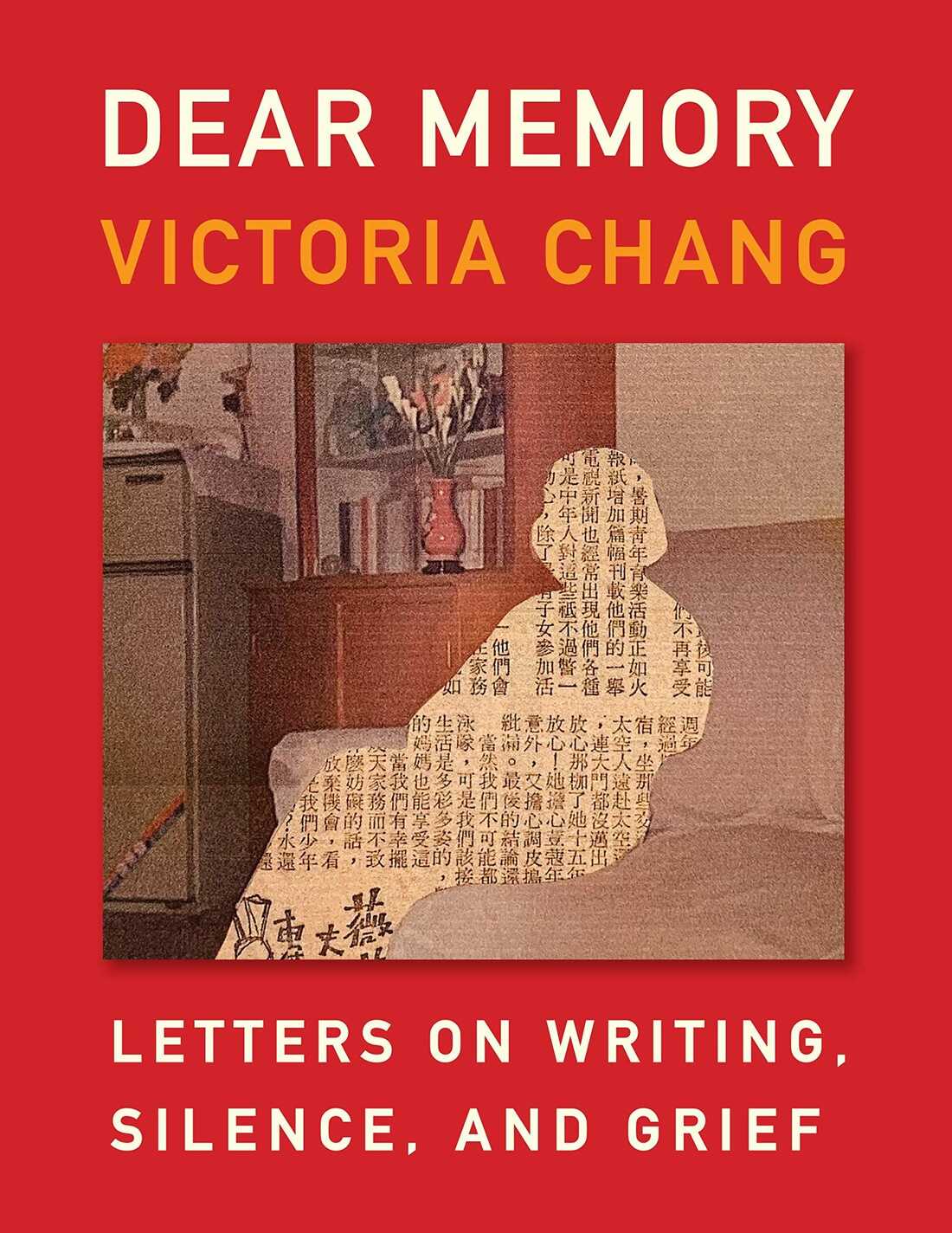

Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief, by Victoria Chang

Milkweed

hide caption

toggle caption

Milkweed

Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief, by Victoria Chang

Milkweed

A groundbreaking collage of epistles, mementos, poetry, and literary criticism, Victoria Chang’s Dear Memory asks a profound question: “Can memory be / unhoused, or is it / the form in which / everything is held?”

Resuming the expressively compressed approach of her 2020 Obit, the poet’s latest work represents a dual articulation of remembrance and creation, as if “[e]ach word, a clavicle, a femur, [and] each sentence, an organ.” In defining language as the nucleus for experience, Chang’s innovative montage brings to mind Jorge Luis Borges’ The Aleph — a haunting story that reconciles mortality with the creative imagination via a point in space — where time and memory are converged as omniscient reality.

While structurally complex, Dear Memory articulates grief’s basic anxieties, “The things that didn’t matter at the time are often the most urgent questions after someone has died.” A person’s mental decline or death can exacerbate the preexisting norms of silence within his or her family — silence caused by shame, trauma, ignorance, language, and cultural attitudes. In this instance, Chang was able to interview her mother Jeng Jin and learn facts about her life in Taiwan and subsequent immigration to the U.S before the latter’s death from pulmonary fibrosis. However, the poet’s father — a former project engineer at Ford Motor Company — had refused to speak about his past, deeming such dialogue “useless” shortly before suffering a debilitating stroke that damaged his frontal lobe.

While most of the book’s biographical elements are based on Jeng Jin’s recollection, Chang can’t allay the sense that her mother’s mementos — official documents translated into English for immigration and naturalization purposes long after the original events occurred — appear insubstantial, performative: “Mother had a photocopy of each of these documents. And then she made another copy of the copies. So many copies to forget her past.” Without reliable narrators or corroborating witnesses, Chang’s family history seems both elusive and static. While loud language resounded in her childhood home — “bundles of Mandarin from Mother’s mouth, Father’s nearly perfect English … [t]hen our Chinglish” — emotional silence “arranged itself like furniture.”

Defining memory as being “shaped by motion, movement, and migration,” Chang sees a direct connection between memory and identity formation. An immigrant’s identity is spliced by displacement, her cultural memory suppressed, “So much of our identity is based on how others … want us to behave, to dress, to talk, how others perceive Chinese food. All the expectations, all the way down to the [menu’s] font.” Nevertheless, Chang sees her immigrant parents’ resolve to assimilate to American culture as economic, not political or cultural: “Resolve is a live animal. We perpetuate the narrative that is given to us in order to survive.”

Chang’s poignant anecdotes on motherhood, from her own experience and others’, can be read as tangible ways to illustrate memory’s paradoxes. An immigrant’s conscious resolve to form new memory is analogous to the decision to nurture an accidental adoptee. Jeng Jin told her daughter how a woman, aboard a boat fleeing Communist China and realizing too late that she had grasped the hand of someone else’s child during the jostle, decided nonetheless to remain with the child. At the same time, losing the vital links to one’s existence can feel like suffering a miscarriage – to have a memory expulsed, “unhoused.”

To resist the corrosive nature of memory/history that seems to murder the past each time it is recalled, Chang employs language as both dissecting scalpel and unifying tool, linking her cultural dislocation to those still suffering the consequences of discrimination. Implicitly dismantling the imperialist view of memory in Robert Frost’s “The Gift Outright” — that “the land was ours before we were the land’s” — Chang retorts, “This land is a facade for the land I really come from. There are lands behind lands.” Rejecting manifest destiny — the notion of America as, in Frost’s descriptive terms, “unstoried, artless, unenhanced” waiting to be found — Chang caustically reminds us of the artist’s dual responsibility: to remain vigilant against revisionist narratives based on political expediency, while being receptive to new ways of assessing the past’s influence on the present.

One of Chang’s recurring concerns is transgenerational trauma — the idea that her parents’ imperfect assimilation has been passed down to subsequent generations as a psychological defect, with unforeseen manifestations due to its unstable relationship to memory. But to view one’s nonconformance as a mental handicap is once again succumbing to the myth of monolithic culture. Chang resolves her anxiety by recasting the ideal of E pluribus unum, “Maybe my children are already American, but a different kind of American. And maybe my children are not really themselves. They’re thousands of years of other people. Cultures. My trauma. Mother’s trauma. Father’s trauma. Their silence. Passed down through me.”

Like Borges’ notion of oneness as embodied by the letter aleph א in the Hebrew alphabet, Dear Memory achieves the holistic concept of yuánmăn 圆满 — roundness, completion, arrival — by dispassionately exploring its antitheses: gaps, severance, and departure. In this sense, Chang’s lyrical experiment memorably evokes an individual family’s time capsule and an artist’s timeless yearning to shape carbon dust into incandescent gem.

Thúy Đinh is a freelance critic and literary translator. Her work can be found at thuydinhwriter.com. She tweets @ThuyTBDinh.