Should your neighborhood be afraid?

Ghost kitchens: Should your neighborhood be afraid?

Ghost Kitchens are the next big tech concept disrupting the restaurant industry. Neighbors on one North Center block say ghost kitchens are disrupting their life.

CHICAGO – You’ve got your phone in your hand, a medium pizza in your cart, and a hunger in your stomach. Once you hit the “place order” button on your delivery app, you are probably not thinking about where your order is going. Increasingly, it is not going to a place with red pepper shakers and tablecloths, but to something called a ghost kitchen. You can also call them dark or virtual kitchens. But they are all the same: a restaurant without a dining room, cooking food solely for a GrubHub world.

Think of a ghost kitchen like an apartment complex for restaurants. A delivery-only food court that is optimized for apps like Grubhub and DoorDash. Ghost kitchen companies divvy up the space, set up kitchen equipment, handle supply chains, perform maintenance, cut through regulatory red-tape, and, most importantly, manage orders from the horde of delivery apps. No dining room. No wait staff. Just gear and infrastructure to get food out the door.

Fast food companies like them because they can push delivery hard without bringing extra traffic to their stores. Smaller restaurants like them because ditching the dining room saves a lot of cash. It has been a lifeline for thousands of small restaurants who lost their dining rooms during the lockdown. The startup costs are low, taking risk out of an industry where failure is the norm. Entrepreneurs like them because they can test multiple food menus in one space. So that pizza order may be going to a kitchen that is cooking as a Chinese restaurant and a barbeque restaurant at the same time.

Shared kitchens brought in $300 million dollars in revenue last year. The concept has been around for a while but exploded in popularity during the delivery-driven COVID-19 lockdown. Analysts forecast a trillion dollars in global sales within the next decade.

SIGN UP FOR EMAIL UPDATES FROM FOX 32 NEWS

But to get to that magic trillion-dollar figure, the industry has will have to endure growing pains.

Which brings us to the 4000 block of North Rockwell Avenue, just north of Irving Park Road in Chicago’s North Center neighborhood. It is here among the row homes, dog lovers, and one-way streets that the future of food service is playing out — one car at a time.

Rockwell Food Center, a ghost kitchen facility owned and operated by Los Angeles-based CloudKitchens, opened on the block in the middle of 2020. Neighbors and neighboring businesses have been pushing back on the company since day one. They claim a major quality-of-life downgrade since Rockwell set up shop.

“Third party delivery drivers will line up in that area. They’ll try to find a parking space that will let them hop out, run into CloudKitchens, pick up their order, and go back to their car,” said Alex Hernandez, a reporter for Block Club Chicago who has covered the neighborhood extensively. “You have two directions of cars on a two-way street trying to find parking directly in front of CloudKitchens. And that’s at the same time as people dropping of a dog at the vet or picking up beer at the brewery down the street.”

The business model for ghost kitchens is volume. The facilities need to blow through dozens of deliveries an hour to be profitable. That’s a lot of cars. Unlike Rockwell Food Center, most ghost kitchen facilities are in industrial and manufacturing areas. Big spaces tucked away in areas close to highways and can handle lots of traffic. The problem for Rockwell is the block is not built for that volume of traffic.

Compounding the problem is the blocks of single-family homes and courtyard apartment buildings which make up the Horner Park neighborhood surrounding Rockwell Food Center. The streets around the area are narrow and many are one-way, which does not lend to traffic flow. Rockwell’s proximity to the Chicago River presents another traffic chokepoint. Alderman Matt Martin, whose 47th Ward incorporates Horner Park, said the complex make-up of the neighborhood makes it tough to play traffic cop.

“There is a very small-scale infrastructure in terms of what the streets will tolerate. There’s also public safety issues, often involving verbal altercations between the third-party delivery drivers, residents, and the other business owners on the block.”

“One neighbor who lives on the block compared it to a Portillos drive-thru. Anyone in Chicago who has gone to Portillos has been in their drive thru. It’s a snake-like, windy thing to go through to get your food,” said Hernandez. “You have dog owners taking their dog to the vet. At the same time, you have third party delivery drivers picking up food, the speed with which they deliver the food is tied to their livelihood. You have this mix of everyone seeking parking on this block. This creates the Portillo’s level log jam on a two-lane street next to this residential property.”

Zoning issues further complicate the issue. The stretch of North Rockwell Ave. is zoned for light manufacturing. CloudKitchens claims this makes Rockwell Food Center no different than the brewery or tool manufacturing company down the street. Blocks like this are common in the north side of Chicago, where compounds of older factories and warehouses have found new life as condos or retail store fronts, with some vestiges of wholesalers and manufacturing remaining in the neighborhood. You could find a glass fabricator sandwiched between a furniture store and a loft apartment complex on some of these blocks. You also would not know the difference because they share the same distressed industrial façade.

CloudKitchens is the biggest player in the shared kitchens industry with a $5 billion dollar valuation and former Uber CEO Travis Kalanick at the head of the table. Rockwell Food Center is CloudKitchens’ fifth facility in Chicago, but it is the only one smack dab in the neighborhood it serves. Deidra Suber, CloudKitchens’ Chicago general manager, says what is happening on Rockwell Ave. is unique to the company.

“We have 32 current live facilities in the United States. And the situation at Rockwell is the only one that we’re having a conflict between us and the community. Like in any business environment, yes, there are tradeoffs. Our buildings bring cars. But we’re also providing food to a community a lot quicker. To use Rockwell for an example over fifty percent of our orders is less than a mile away. It’s not like this food is being shipped downtown or to the south side.”

CloudKitchens’ biggest defense is it kept local restaurants in business during the lengthy Covid-19 lockdown. One local restaurateur who found a lifeline as Rockwell is Lisa Yeoun, the former owner of Shanghai Inn in Ravenswood, a neighborhood close to Rockwell.

“We were closed for three and a half months. I didn’t know where things were going. It was all very unexpected. The future’s very bleak. My lease is coming up.”

Yeoun was facing both financial pressure and racial harassment at the time and started questioning her future early during the pandemic.

“We have people calling us. ‘We don’t want Asian people or Chinese people to bring our food out to us.’ Two days later someone calls us. ‘How long has your cook been in the kitchen? Did he go back to China?’ I get phone calls over and over. ‘Go back to China.’ I felt like I was being interrogated. I was just drained. Should I give it up? I should retire!”

Yeoun sold Shanghai Inn but quickly found retirement did not suit her. She missed cooking and found herself back at business at Rockwell. Suber claimed the ghost kitchen business model was built to help a restaurateur like Yeoun.

“She comes in. She unlocks her space. She cooks the food for her customers. I’m taking care of pests, water, If there’s an outage. I take care of internet. There’s an extra layer of comfort that there’s going to be fewer unknowns in our space because my team is taking care of that.”

“It’s been four months. Revenue’s doing pretty good,” Yeoun said. “It’s safe. Everything is up to code. New equipment. I don’t have to clean a dining room. There’s no cash at night. It saves a lot of overhead. It is a very great concept. This is going to be the future kitchen.”

That does not sit well with other players in the Chicago restaurant scene. Chicago restaurateur Scott Weiner is fighting to prevent a future where restaurants need technology companies to survive.

“Restaurants are being squeezed. I am in a real fortunate situation where once dining recovers, I have big restaurants and delivery is not all my business. But the small guy on the street – the small pizza place with ten fifteen seats — that is probably 75 to 85 percent of their business. If that’s coming from a third-party delivery service now it’s sort of chipping that away.”

Weiner owns the Fifty/50 Restaurant Group, home to Chicago favorites such as Roots Handmade Pizza and West Town Bakery. He has been trying to beat the tech companies at their own game by creating his own payment apps and employing his own delivery drivers. Yet, he said he is nowhere close to a level playing field.

“If you search Roots Pizza [on Google], ads for Grub Hub and Door Dash will come up to try to steal you to their page instead of coming direct to me. I don’t have a $300 million marketing budget. I have a budget and it’s not insignificant, but I’m spending half my budget defending my own name. The reality is I run out of my budget and their budget is unlimited.”

Weiner is also concerned about what Chicago will look like if restaurants start moving out of neighborhoods and into warehouses.

“The things that make neighborhoods vibrant and grow is the restaurants and the retail in the neighborhood. Restaurants are the things that create growth in neighborhoods. If you can just open up ghost kitchen concepts in a manufacturing area it just doesn’t make sense to have any retail on these main streets and the fabric of our neighborhoods is going to die.”

That is not a pretty picture. But Mott Smith and Brian Albert from Amped Kitchens, a virtual kitchen company based in Los Angeles, say you avoid that nightmare by investing in the neighborhood while you’re setting up shop.

“When our facilities come into places it has a kind of stabilizing effect on the community because we’re a real presence. Making a neighborhood feel like a neighborhood,” said Albert, Amped Kitchens’ co-owner and CMO.

“Our passion has always been about lifting up communities that are emerging,” added Smith, Amped Kitchens’ co-owner and CEO. “Maybe they have a good soul and a cool infrastructure, but something hasn’t yet caught on. Some spark hasn’t happened.”

Amped Kitchens has two locations in Los Angeles and recently opened their third in Chicago: a former Zenith factory in Chicago’s Belmont Cragin neighborhood.

“We love restoring old buildings,” said Smith. “We love finding big open shells that have been open and vacant for years and put new life in them. Our three locations have been former warehouses. Our two In LA were actual warehouses that may have had six to twelve jobs and by the time our tenants moved in there were two to three hundred jobs on site. “

Amped Kitchens focuses more on food manufacturing than quick delivery, opening their space to emerging entrepreneurs who have outgrown their home kitchen.

“Someone starting a new food product or new food business can expect to spend twelve to fourteen months and up to $500 thousand dollars at the bottom end,” said Smith. “If your goal is to sell your family’s bread recipe that a recipe for disaster. We make it possible to say yes to that opportunity to sell your product for the first time at Whole Foods without a million dollars in the bank and without being able to go without money for a year.”

That is the story of Jars by Jasiman, a married team of dessert lovers who have set up shop at CloudKitchens’ South Loop location. For Jasiman Griffin-Green and Rasheed Green, the concept came naturally.

“I have always been a sweet lover,” said Griffin-Green. “I have a friend who runs a restaurant in the city. She needed desserts. She asked me to help her restaurant. We did well and I thought this could be something here. This is how we got to the concept of Jars by Jasiman. We worked out of our home for two years. We wanted to take it to the professional level. So, we came to CloudKitchens to get our space and it’s worked out well.”

Jars by Jasiman’s most popular products are creative takes on banana pudding packaged in convenient glass jars. They focus on getting desserts into retail stores, but they also do catering and delivery out of the same shared kitchen, allowing them to greatly expand their customer base beyond Chicago’s South Side.

CloudKitchens encourages their partners to diversify beyond quick delivery. A business like Jars by Jasiman would be tough for two people to run out of a brick-and-mortar shop. And even tougher in the kind of underserved communities in which both Amped Kitchens and CloudKitchens set up shop.

“We also provide a really equitable was for small entrepreneur who may not have access to start a business,” said Suber.

“In our south Los Angeles location what we have seen is a ton of black owned businesses. People who live in that neighborhood have developed successful businesses,” said Albert. “We see a ton of people from that community who just needed that next step.”

It is a nice vision. Will all the players on North Rockwell Ave. be able to get there? Both sides have been trying to work it out, but it has been a tug-of-war.

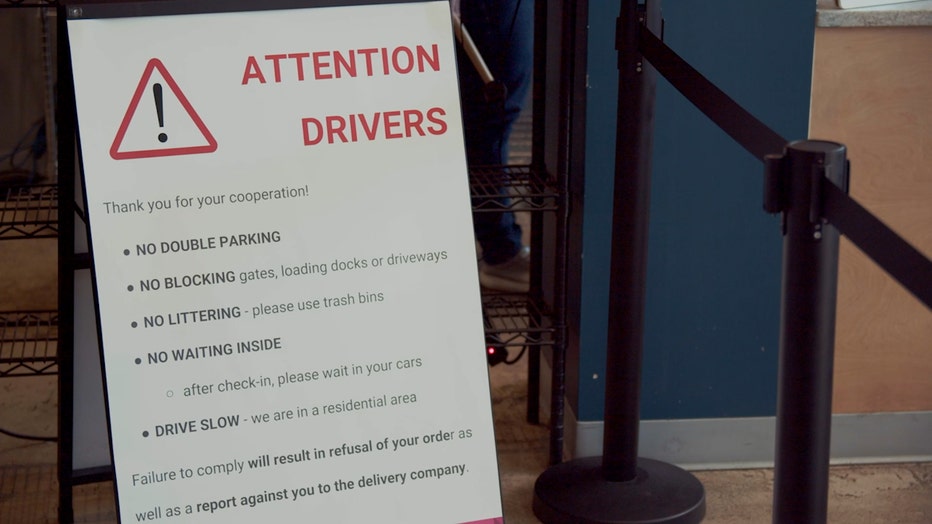

After many tense public meetings, CloudKitchens developed a plan which focuses on thinning traffic, giving drivers their own parking spaces off the street, and setting up a runner system to keep drivers in their cars.

Those changes have lightened the traffic flow in the area. But now, neighbors are pushing Alderman Martin to get in front of future issues. A promise on the top of their list: a second fast food chain will not wind up at Rockwell.

“We started seeing a significant uptick in traffic and parking related complaints when Chik-Fil-A started operating,” said Martin. “That is not a locally owned and operated business that needs help in the form of a shared kitchens concept to get off the ground.”

The fast-food favorite is blamed for most of the traffic on the block, as well as an increase in litter and a lingering chicken odor in the air. Rockwell Food Center is not operating capacity and neighbors fear adding a second high-volume fast-food joint in the future will make any current plan obsolete. CloudKitchens will not make that promise saying it does not make business sense. So, the meetings continue, even though both sides are ready to get the check.

Alex Hernandez has endured many of those meetings.

“It’s a point of frustration. These are hours long meetings. All these meetings since January – one a month – it is the same attempt at resolution. And at the end of the meeting, ‘we’re going to meet next month.’ Everyone is on board, but they’re fed up with these meetings. They want some kind of resolution for these meetings to end.”

Chicago’s Business Affairs and Consumer Protection department has been running these meetings since 2019. Neighbors say the agency is wasting their time because they do not have the muscle to affect real change. They are pushing Alderman Martin to take their case to the people who run the roads: the Chicago Department of Transportation.

CloudKitchens is going in a different direction. They are taking their operators out of the kitchen and in front of the people, making the case that it’s the North Rockwell Ave. neighbors who are threatening small businesses. That effort launched in late April when Suber, Yeoun, and a host of other operators appeared in front of Alderman Martin’s office for a pop-up protest.

“They’re in a very tough industry. I wanted to give them an opportunity to share their voice. I think it’s important to know what these conversations are going to directly impact and it’s going to be these small and medium business owners.”

If North Rockwell Ave. holds a lesson, it is that cities and states are ill equipped to help the shared kitchen industry navigate inevitable growing pains.

“Nobody knows if you say virtual or cloud kitchen what any of that means. And that’s a problem right now because not even the city of Chicago knows what that means,” said Weiner.

“The city of Chicago has rules about how many nail salons near each other. If you want to open a liquor store there are rules in place for a liquor licenses to allow for community buy-in,” said Hernandez. “When it comes to cloud kitchens or ghost kitchens, the city doesn’t have the legislative vocabulary to fit this business into its existing system with other business licenses.”

“Let’s take a fresh look at zoning code. How we want to adjust these because it is a very novel business model. We want to be able to see around the curve now that we know what is coming. So I would encourage anybody in any part of the country… to take a look at what folks can do as a right so you’re not in the position we’re in which is forced to be reactive.”